When you think of Parisian cinema, you probably picture classic black-and-white films by Truffaut or Godard. But there’s another thread running through the city’s underground film scene-one that’s raw, unapologetic, and quietly revolutionary. That thread is HPG.

What HPG Really Is

HPG doesn’t stand for anything official. No press release, no website, no corporate logo. It’s a name whispered in backrooms of Le Marais cinemas, scribbled on film canisters in Montmartre basements, and stamped on bootleg DVDs sold outside Métro stations. Some say it’s short for Hors de Paris, Génération-outside Paris, generation. Others insist it’s just the initials of a forgotten filmmaker who vanished after his first film was banned in 1998. The truth? It doesn’t matter. HPG is a vibe, not a label.

What defines HPG isn’t the plot or the actors-it’s the way it looks. Grainy 16mm film. Natural light. No studio lighting. No rehearsed lines. Actors often aren’t actors at all. They’re students, bartenders, ex-convicts, poets. The camera doesn’t glide-it stumbles. It lingers on cracked walls, empty cafés at 3 a.m., and hands lighting cigarettes in silence.

One of the earliest known HPG films, Le Dernier Bus à Montparnasse (2001), was shot over three weeks with a borrowed camera and a 200-euro budget. It had no soundtrack. No credits. Just 72 minutes of a woman walking the same street every day, watching the same man sell newspapers, until one day he’s gone. It screened once-at a friend’s apartment-and was never officially released. Yet it’s been downloaded over 800,000 times on obscure forums.

The HPG Aesthetic

HPG films reject polish. They don’t want you to be impressed. They want you to feel uncomfortable. You’re not supposed to enjoy them. You’re supposed to wonder why you’re still watching.

There’s no hero. No arc. No resolution. Characters disappear mid-scene. Dialogue is sparse, often in dialects you can’t place-Algerian Arabic mixed with Parisian slang, or the broken French of Senegalese immigrants who’ve lived in the 18th arrondissement for 40 years but still don’t sound like locals.

The most striking thing about HPG is its use of silence. Not the kind you hear in arthouse films where silence is carefully composed. HPG silence is messy. You hear distant sirens. A neighbor arguing. A child crying. A fridge humming. In one scene from Les Murs Ont Soufflé (2014), a man sits on a fire escape for 11 minutes. He doesn’t move. He doesn’t speak. The camera doesn’t cut. You hear his breathing. Then, at exactly 11:03, he stands up, walks inside, and closes the door. That’s the whole film.

Sound design? Almost none. Music is forbidden. If a song appears, it’s because someone left a radio on in the background. No score. No swelling strings. No emotional cues. You’re left alone with your thoughts-and that’s the point.

Who Makes HPG Films?

There’s no HPG studio. No funding body. No film school that teaches it. The people behind HPG films are usually under 30, have no formal training, and work day jobs to pay for film stock. Many are women. Many are immigrants. Many have never been to a film festival.

One filmmaker, known only as Marie 17, shot her first film in her mother’s apartment in Saint-Denis. She used a GoPro taped to a broomstick. The film, Le Lit de Maman, shows her mother sleeping, waking, eating, crying, and talking to herself in a mix of French and Kabyle. It was uploaded to a private Vimeo link in 2019. Three years later, it was screened at the Cannes Critics’ Week-without permission. The organizers didn’t know who made it. They just found it.

Another HPG figure, a former street artist named Lucas G., began filming homeless men in the 13th arrondissement. He didn’t interview them. He didn’t ask for stories. He just pointed the camera and let them exist. His 2021 film, Les Hommes du Pont, was later described by Le Monde as “the most honest portrait of urban isolation in modern France.” Lucas still lives in a squat in Belleville. He doesn’t own a computer.

Why HPG Matters

Paris has a thousand film movements. Nouvelle Vague. Cinéma du Look. French New Wave 2.0. But HPG is different. It doesn’t want to be seen. It doesn’t want to win awards. It doesn’t want to be remembered.

It exists because the people making it have nothing else. No platform. No voice. No money. So they make films with whatever they have-a phone, a camera, a friend’s apartment, a stolen roll of film. And somehow, those films become more real than anything you’ll see on Netflix or at the Cinémathèque Française.

HPG films don’t tell you about poverty. They show you the exact way a single mother folds her last pair of socks before leaving for work. They don’t preach about immigration. They show a Moroccan grandmother humming a lullaby in Darija while scrubbing floors in a Parisian office building at 5 a.m.

In a city obsessed with style, HPG is the anti-style. It’s the glitch in the system. The static on the radio. The unfinished sentence.

Where to Find HPG Films

You won’t find HPG on streaming services. You won’t find it on IMDb. You won’t find it in bookstores. You find it the way people found punk tapes in the 80s: through word of mouth, hidden links, and trusted friends.

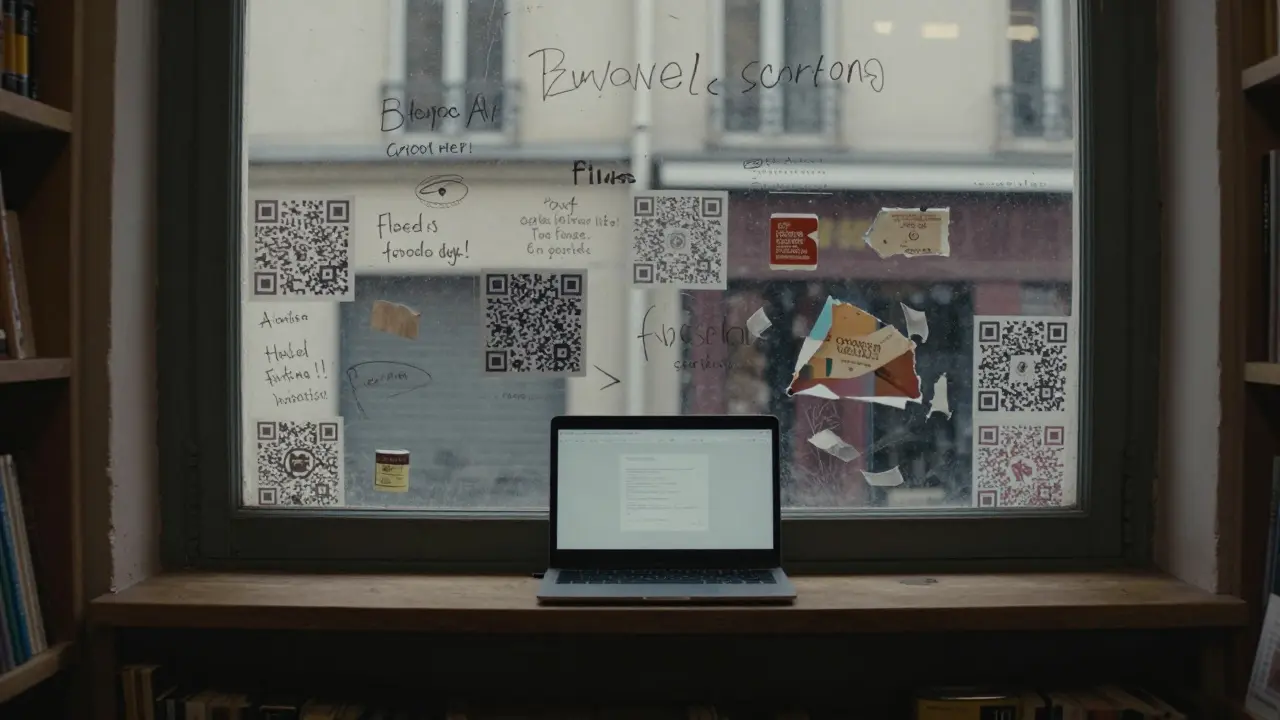

There’s a Telegram group called HPG Archive with 12,000 members. It’s password-protected. The password changes every week. It’s posted on a single wall in the back of a bookstore in the 10th arrondissement-Librairie des Écrivains Clandestins. The wall is covered in handwritten notes, film titles, and QR codes. No one knows who runs the group. No one asks.

Some films surface on YouTube under random titles: Paris 2007 - No Sound, Woman in the Stairwell, 12 Minutes of Rain. They’re usually taken down within 48 hours. But someone always uploads them again.

If you want to see HPG, you have to be willing to look in the wrong places. You have to be okay with not knowing what you’re watching. You have to accept that you might not understand it. That’s the rule.

Is HPG Still Alive?

Yes. And it’s changing.

Some filmmakers are now using AI to restore old HPG footage-cleaning up grain, stabilizing shaky shots. Purists hate it. They call it betrayal. But others argue it’s the only way these films survive. Without restoration, the 16mm reels are rotting. The tapes are fading.

There’s talk of a museum exhibit in 2026 at the Palais de Tokyo. Rumor has it they’ve collected 47 HPG films. But no one knows which ones. No one knows who approved them. No one knows if they’ll even show up.

What’s certain is this: HPG will never be mainstream. It doesn’t want to be. It was never meant to be. It’s the quiet rebellion of people who have nothing to lose and everything to show. And in a world where every frame is curated, every emotion is monetized, and every story is packaged-that’s the most radical thing left.

How to Start Your Own HPG Film

You don’t need a camera. You don’t need actors. You don’t need a script.

Here’s how to begin:

- Find a place where no one is supposed to film. A laundry room. A subway tunnel. A hospital hallway at night.

- Turn off all lights. Use only natural or existing light.

- Record for at least 10 minutes. Don’t stop. Don’t edit.

- Don’t ask anyone to speak. Don’t explain anything.

- Upload it under a random name. No credits. No description.

- Wait. If someone finds it, they’ll know.

That’s it. That’s HPG.